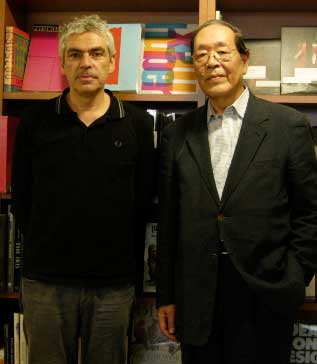

photo: Tomoo Karube photo: Tomoo Karube

It was a beautiful, chilly morning in late October.

The sun was shining and the skies were blue over Tokyo Station. Professor Hasumi, a tall man in a long overcoat, was already waiting for

me on the Shinkansen platform, a brown leather

briefcase closely clutched between his hands.

There was the most charming and mysterious smile on his face.

I had read his book on Yasujiro Ozu,

and therefore I was drawn to like the man. I even imagined I already knew him a

bit, and, through him, his country and his fellow countrymen.

He had seen some of my films; perhaps there was a chance he could feel some

sympathy for me. But, most of all, at that moment, I realised how lucky I was: for the next three hours, I had the privilege of having

Professor Hasumi as my travelling companion. I was at

his mercy, so to speak; I had already trusted him on Ozu and

now I could confirm his Japan and

compare it with my Japan, unfolding

outside the window.

As the train gathered speed, I began considering what I secretly called the ‘Hasumi paradox’. Although he is considered a very special

writer, there's something that really sets him apart from the rest: adopting a

reluctant methodology, his is a very different way of observing the world and

human beings in cinema; his account, his description of a film, is

completely unique and somewhat dissident to those of most cinema

critics.

The strength he finds in Ozu or Ford or Hawks? An absolute confidence in the world, in our world, through the power of cinema. A conviction.

We could say that Hasumi doesn’t write from a critic’s

point of view; he writes from a filmmaker’s point of view. In every text, about

whichever film, we really feel that he is speaking from ‘inside’ the film, not

from a distance or from the outside.

It’s our own, filmmaker's work he’s doing when he is thinking and writing about

a film.

To describe a film he has to consider all the concrete problems we also deal

with. His account is materialistic and precise: how to guide an actor through a

limited space, how to speed up or slow down a certain gesture or action of his

body, how to tackle or compose or just fiddle with your frame, how to balance a

sequence of contradictory nervous tensions? Hasumi writes about all of this as only a filmmaker would. Probably, he wouldn’t

approve, but the obvious conclusion is that he works just like a filmmaker.

Professor Hasumi does not want to reveal

anything.

He confirms, he sustains; he’s just like a companion to the films he praises.

Jacques Rivette’s definition of cinema is also his

own: a bond between something exterior and something secret that an unexpected

gesture reveals without explaining.

Every time I read something by Hasumi, he never

ceases to hold tight to this secret gift.

Leaving

behind the city of Sendai, I remembered that his book on Ozu was divided into chapters or sections entitled ‘to eat’, ‘to change clothes’,

‘to see’, ‘to live’, ‘to stop’ ...

I wondered what Roberto Rossellini would have thought of this.

The author of India Matri Bhumi used to say

that, to make a film, all you had to do was to draw a diagram on a blackboard

and write down ‘food’, ‘clothing’, ‘domestic habits’, ‘weather’, every

detail you could gather from a serious observation of a determined community or

country. This would be your screenplay, all abstraction and unnecessary poetry

removed, and the film would be ready to shoot.

To make a film, to write about a film.

I

was lost in these musings; between the beautiful vistas on my left and the

serene passenger in front, between my memory of his splendid, exact writings

and the wonderful matching materiality of the Japan I saw through the train

windows: peasants working the fields, the roofs of old houses, the tiny vans,

the colour of trees, the bridges over the rivers, the

writings on signs ...

And our three hours just sped by ...

I realised I had been silent for most of the journey ...

Being such a masterful observer, Professor Hasumi had

no doubt resigned to my taciturn, melancholic nature.

A bit ashamed, I excused myself for being such a dull companion.

In a gentle, deep voice he said that Mikio Naruse was a very silent man:

‘Because he had the feeling that the world had betrayed him’.

Naruse, Ozu, Hasumi: men who speak softly of our weaknesses.

|

|

|